Applications of Integration

Area Between Curves

The area between the graphs of two functions is equal to the integral of a function, [latex]f(x)[/latex], minus the integral of the other function, [latex]g(x)[/latex]: [latex]A = \int_a^{b} ( f(x) - g(x) ) \, dx[/latex].Learning Objectives

Evaluate the area between two functions using a difference of definite integralsKey Takeaways

Key Points

- Area is a quantity that expresses the extent of a two-dimensional surface or shape, or planar lamina, in the plane.

- The area between the graphs of two functions is equal to the integral of one function, [latex]f(x)[/latex], minus the integral of the other function, [latex]g(x)[/latex]:[latex]A = \int_a^{b} ( f(x) - g(x) ) \, dx[/latex] where [latex]f(x)[/latex] is the curve with the greater y-value.

- The area between a positive-valued curve and the horizontal axis, measured between two values, [latex]a[/latex] and [latex]b[/latex] (where [latex]b>a[/latex]), on the horizontal axis, is given by the integral from [latex]a[/latex] to [latex]b[/latex] of the function that represents the curve: [latex]A = \int_a^{b} f(x) \, dx[/latex].

Key Terms

- area: a measure of the extent of a surface measured in square units

- curve: a simple figure containing no straight portions and no angles

- axis: a fixed, one-dimensional figure, such as a line or arc, with an origin and orientation and such that its points are in one-to-one correspondence with a set of numbers; an axis forms part of the basis of a space or is used to position and locate data in a graph (a coordinate axis)

Area Between Curves

The area between a positive-valued curve and the horizontal axis, measured between two values [latex]a[/latex] and [latex]b[/latex] ([latex]b[/latex] is defined as the larger of the two values) on the horizontal axis, is given by the integral from [latex]a[/latex] to [latex]b[/latex] of the function that represents the curve. The area between the graphs of two functions is equal to the integral of one function, [latex]f(x)[/latex], minus the integral of the other function, [latex]g(x)[/latex]:[latex]A=\int_a^{b}(f(x)−g(x))\,dx[/latex] where [latex]f(x)[/latex] is the curve with the greater y-value.

Area Between Two Graphs: The area between two graphs can be evaluated by calculating the difference between the integrals of the two functions.

Integration: Area Under a Curve: Integration can be thought of as measuring the area under a curve, defined by [latex]f(x)[/latex], between two points (here, [latex]a[/latex] and [latex]b[/latex]).

Example

Find the area between the two curves [latex]f(x)=x[/latex] and [latex]f(x)= 0.5 \cdot x^2[/latex] over the interval from [latex]x=0[/latex] to [latex]x=2[/latex]. Two curves, [latex]y=x[/latex] and [latex]y = 0.5 \cdot x^2[/latex], meet at the points [latex](x_0,y_0)=(0,0) [/latex] and [latex](x_1,y_1)=(2,2)[/latex]. Since [latex]x > 0.5 \cdot x^2[/latex] over the interval from [latex]x=0[/latex] to [latex]x=2[/latex], the area can be calculated as follows: [latex-display]\displaystyle{A = \int_0^{2} ( x - \frac{1}{2} x^2 ) \, dx = \left [ \frac{1}{2} x^2- \frac{1}{6} x^3 \right ]_{x=0}^{x=2} = \frac{2}{3}}[/latex-display]Volumes

Volumes of complicated shapes can be calculated using integral calculus if a formula exists for the shape's boundary.Learning Objectives

Calculate the volume of a shape by using the triple integral of the constant function 1Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Volume is the quantity of three-dimensional space enclosed by some closed boundary—for example, the space that a substance or shape occupies or contains.

- Volumes of some simple shapes, such as regular, straight-edged, and circular shapes can be easily calculated using arithmetic formulas.

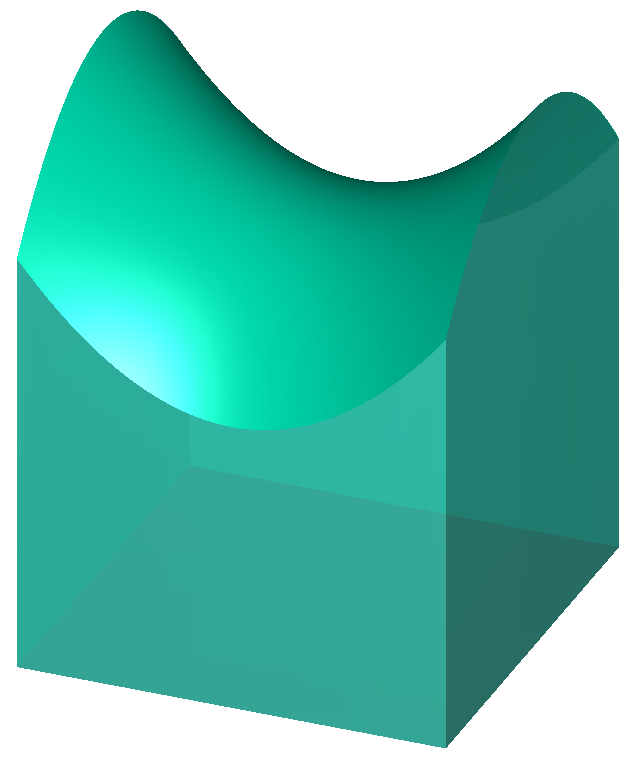

- Volumes of complicated shapes can be calculated using a triple integral of the constant function [latex]1[/latex]: [latex]\text{volume}(D)=\int\int\int\limits_D dx\,dy\,dz[/latex].

Key Terms

- cuboid: a parallelepiped having six rectangular faces

- volume: a unit of three-dimensional measure of space that comprises a length, a width and a height; measured in units of cubic centimeters in metric, cubic inches, or cubic feet in English measurement

- integral: also sometimes called antiderivative; the limit of the sums computed in a process in which the domain of a function is divided into small subsets and a possibly nominal value of the function on each subset is multiplied by the measure of that subset, all these products then being summed

Fig 1: Triple integral of a constant function [latex]1[/latex] over the shaded region gives the volume.

Example

The volume of the cuboid with side lengths 4, 5, and 6 may be obtained in either of two ways.Method 1

Using the triple integral given above, the volume is equal to: [latex-display]\displaystyle{\iiint_\mathrm{cuboid} 1 \, dx\, dy\, dz}[/latex-display] of the constant function [latex]1[/latex] calculated on the cuboid itself. This yields: [latex-display]\displaystyle{\int_{z=0}^{z=5} \int_{y=0}^{z=6} \int_{x=0}^{x=4} 1 \, dx\, dy\, dz = 120}[/latex-display]Method 2

Alternatively, we can use the double integral: [latex-display]\displaystyle{\iint_D 5 \ dx\, dy}[/latex-display] of the function [latex]z = f(x, y) = 5[/latex] calculated in the region [latex]D[/latex] in the [latex]xy[/latex]-plane, which is the base of the cuboid. For example, if a rectangular base of such a cuboid is given via the [latex]xy[/latex] inequalities [latex]3 \leq x \leq 7[/latex], [latex]4 \leq y \leq 10[/latex], our above double integral now reads: [latex-display]\displaystyle{\int_4^{10}\left( \int_3^7 \ 5 \ dx\right) dy =120}[/latex-display] This is the volume under the surface.Average Value of a Function

The average of a function [latex]f(x)[/latex] over an interval [latex][a,b][/latex] is [latex]\bar f = \frac{1}{b-a} \int_a^b f(x) \ dx[/latex].Learning Objectives

Evaluate the average value of a function over a closed interval using integrationKey Takeaways

Key Points

- An average is a measure of the "middle" or "typical" value of a data set. It is a measure of central tendency.

- If [latex]n[/latex] numbers are given, each number denoted by [latex]a_i[/latex], where [latex]i = 1, \cdots, n[/latex], the arithmetic mean is the sum of all [latex]a_i[/latex] values divided by [latex]n[/latex]: [latex]AM=\frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^na_i[/latex].

- An average of a function is equal to the area under the curve, [latex]S[/latex], divided by the range.

Key Terms

- average: any measure of central tendency, especially any mean, median, or mode

- function: a relation in which each element of the domain is associated with exactly one element of the co-domain

- arithmetic mean: the measure of central tendency of a set of values, computed by dividing the sum of the values by their number; commonly called the mean or the average

Fig 1: The average of a function [latex]f(x)[/latex] that has area [latex]S[/latex] over the range [latex][a,b][/latex] is [latex]\frac{S}{b-a}[/latex].

Mean Value Theorem for Integration

The first mean value theorem for integration states that if [latex]G: [a, b] \to R[/latex] is a continuous function and [latex]\varphi[/latex] is an integrable function that does not change sign on the interval [latex](a, b)[/latex], then there exists a number [latex]x[/latex] in [latex](a, b)[/latex] such that: [latex-display]\displaystyle{\int_a^b G(t)\varphi (t) \, dt=G(x) \int_a^b \varphi (t) \, dt}[/latex-display] In particular, if [latex]\varphi(t) = 1[/latex] for all [latex]t[/latex] in [latex][a, b] [/latex], then there exists [latex]x[/latex] in [latex](a, b)[/latex] such that: [latex-display]\displaystyle{\int_a^b G(t) \, dt=\ G(x)(b - a)}[/latex-display] The value [latex]G(x)[/latex] is the mean value of [latex]G(t)[/latex] on [latex][a, b] [/latex] as we saw previously.Cylindrical Shells

In the shell method, a function is rotated around an axis and modeled by an infinite number of cylindrical shells, all infinitely thin.Learning Objectives

Use shell integration to create a cylindrical shell and calculate the volume of a "solid of revolution" perpendicular to the axis of revolution.Key Takeaways

Key Points

- The volume of the solid formed by rotating the area between the curves of [latex]f(x)[/latex] and [latex]g(x)[/latex] when integrating perpendicular to the axis of revolution, is [latex]V = 2\pi \int_a^b x \left | f(x) - g(x) \right | \,dx[/latex].

- The integrand in the integral is nothing but the volume of the infinitely thin cylindrical shell.

- Integration, as an accumulative process, calculates the integrated volume of a "family" of shells (a shell being the outer edge of a hollow cylinder ), giving us the total volume.

Key Terms

- cylinder: a surface created by projecting a closed two-dimensional curve along an axis intersecting the plane of the curve

- revolution: rotation: the turning of an object around an axis

- volume: a unit of three-dimensional measure of space that comprises a length, a width and a height; measured in units of cubic centimeters in metric, cubic inches, or cubic feet in English measurement

The Shell Method: Calculating volume using the shell method. Each segment located at [latex]x[/latex], between [latex]f(x)[/latex]and the [latex]x[/latex]-axis, gives a cylindrical shell after revolution around the vertical axis.

Work

Forces may do work on a system. Work done by a force ([latex]F[/latex]) along a trajectory ([latex]C[/latex]) is given as [latex]\int_C \mathbf{F} \cdot d\mathbf{x}[/latex].Learning Objectives

Calculate "work" as the integral of instantaneous power applied along the trajectory of the point of applicationKey Takeaways

Key Points

- The total work along a path is the time- integral of instantaneous power applied along the trajectory of the point of application: [latex]W = \int_{t_1}^{t_2}\mathbf{F} \cdot \mathbf{v}dt[/latex].

- The sum of these small amounts of work over the trajectory of the point yields the work: [latex]W = \int_{t_1}^{t_2}\mathbf{F} \cdot \mathbf{v}dt = \int_{t_1}^{t_2}\mathbf{F} \cdot {\frac{d\mathbf{x}}{dt}}dt =\int_C \mathbf{F} \cdot d\mathbf{x}[/latex].

- For a constant force directed at an angle [latex]\theta[/latex] with the direction of displacement ([latex]d[/latex]), work is given as [latex]W = F \cdot d \cdot \cos\theta[/latex].

Key Terms

- spring constant: a characteristic of a spring which is defined as the ratio of the force affecting the spring to the displacement caused by it

- force: a physical quantity that denotes ability to push, pull, twist or accelerate a body which is measured in a unit dimensioned in [latex]\frac{M \cdot L}{T^2}[/latex] (SI: newton, abbreviated N; CGS: dyne, abbreviated dyn)

Example: Work Done by a Spring

Let's consider an object with mass [latex]m[/latex] attached to an ideal spring with spring constant [latex]k[/latex]. When the object moves from [latex]x=x_0[/latex] to [latex]x=0[/latex], work done by the spring would be: [latex-display]\displaystyle{W = \int_C \mathbf{F_s} \cdot d\mathbf{x} = \int_{x_0}^{0} (-kx)dx = \frac{1}{2} k x_0^2}[/latex-display]

Spring and Restoring Force: The spring applies a restoring force ([latex]-k \cdot x[/latex]) on the object located at [latex]x[/latex]. Work done by the restoring force leads to increase in the kinetic energy of the object.

Volumes of Revolution

Disc and shell methods of integration can be used to find the volume of a solid produced by revolution.Learning Objectives

Distinguish between the disc and shell methods of integration in order to find the volumes of solids produced by revolutionKey Takeaways

Key Points

- A solid of revolution is a solid figure obtained by rotating a plane curve around some straight line (the axis ) that lies on the same plane.

- The disc method is used when the slice that was drawn is perpendicular to the axis of revolution; i.e. when integrating parallel to the axis of revolution.

- The shell method is used when the slice that was drawn is parallel to the axis of revolution; i.e. when integrating perpendicular to the axis of revolution.

Key Terms

- cylinder: a surface created by projecting a closed two-dimensional curve along an axis intersecting the plane of the curve

- integration: the operation of finding the region in the [latex]xy[/latex]-plane bound by the function

- revolution: the turning of an object about an axis

A Volume of Revolution: A solid formed by rotating a curve around an axis.

Disc Method

The disc method is used when the slice that was drawn is perpendicular to the axis of revolution; i.e. when integrating parallel to the axis of revolution. The volume of the solid formed by rotating the area between the curves of [latex]f(x)[/latex] and [latex]g(x)[/latex] and the lines [latex]x=a[/latex] and [latex]x=b[/latex] about the [latex]x[/latex]-axis is given by: [latex]\displaystyle{V = \pi \int_a^b \left | f^2(x) - g^2(x) \right | \,dx}[/latex] If [latex]g(x) = 0[/latex] (e.g. revolving an area between curve and [latex]x[/latex]-axis), this reduces to: [latex-display]\displaystyle{V = \pi \int_a^b f(x)^2 \,dx}[/latex-display]

Disc Integration: Disc integration about the [latex]y[/latex]-axis. Integration is along the axis of revolution ([latex]y[/latex]-axis in this case).

Shell Method

The shell method is used when the slice that was drawn is parallel to the axis of revolution; i.e. when integrating perpendicular to the axis of revolution. The volume of the solid formed by rotating the area between the curves of [latex]f(x)[/latex]and [latex]g(x)[/latex] and the lines [latex]x=a[/latex] and [latex]x=b[/latex] about the [latex]y[/latex]-axis is given by: [latex-display]\displaystyle{V = 2\pi \int_a^b x \left | f(x) - g(x) \right | \,dx}[/latex-display] If [latex]g(x)=0[/latex] (e.g. revolving an area between curve and [latex]x[/latex]-axis), this reduces to: [latex-display]\displaystyle{V = 2\pi \int_a^b x \left | f(x) \right | \,dx}[/latex-display]

Shell Integration: The integration (along the [latex]x[/latex]-axis) is perpendicular to the axis of revolution ([latex]y[/latex]-axis).

Licenses & Attributions

CC licensed content, Shared previously

- Curation and Revision. Provided by: Boundless.com License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike.

CC licensed content, Specific attribution

- Area. Provided by: Wikipedia License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike.

- area. Provided by: Wiktionary License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike.

- curve. Provided by: Wiktionary License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike.

- axis. Provided by: Wiktionary License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike.

- Area. Provided by: Wikipedia License: CC BY: Attribution.

- Area. Provided by: Wikipedia License: CC BY: Attribution.

- Integral calculus. Provided by: Wikipedia Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Integral_calculus. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike.

- Volume. Provided by: Wikipedia License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike.

- volume. Provided by: Wiktionary License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike.

- integral. Provided by: Wiktionary License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike.

- cuboid. Provided by: Wiktionary License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike.

- Area. Provided by: Wikipedia License: CC BY: Attribution.

- Area. Provided by: Wikipedia License: CC BY: Attribution.

- Integral calculus. Provided by: Wikipedia License: CC BY: Attribution.

- Mean value theorem. Provided by: Wikipedia License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike.

- Average. Provided by: Wikipedia License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike.

- function. Provided by: Wiktionary License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike.

- average. Provided by: Wiktionary License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike.

- arithmetic mean. Provided by: Wiktionary License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike.

- Area. Provided by: Wikipedia License: CC BY: Attribution.

- Area. Provided by: Wikipedia License: CC BY: Attribution.

- Integral calculus. Provided by: Wikipedia License: CC BY: Attribution.

- Area. Provided by: Wikipedia License: CC BY: Attribution.

- Volume. Provided by: Wikipedia License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike.

- Solid of revolution. Provided by: Wikipedia License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike.

- cylinder. Provided by: Wiktionary License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike.

- volume. Provided by: Wiktionary License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike.

- revolution. Provided by: Wiktionary License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike.

- Area. Provided by: Wikipedia License: CC BY: Attribution.

- Area. Provided by: Wikipedia License: CC BY: Attribution.

- Integral calculus. Provided by: Wikipedia License: CC BY: Attribution.

- Area. Provided by: Wikipedia License: CC BY: Attribution.

- Shell method. Provided by: Wikipedia License: CC BY: Attribution.

- Work (physics). Provided by: Wikipedia License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike.

- force. Provided by: Wiktionary License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike.

- spring constant. Provided by: Wiktionary License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike.

- Area. Provided by: Wikipedia License: CC BY: Attribution.

- Area. Provided by: Wikipedia License: CC BY: Attribution.

- Integral calculus. Provided by: Wikipedia License: CC BY: Attribution.

- Area. Provided by: Wikipedia License: CC BY: Attribution.

- Shell method. Provided by: Wikipedia License: CC BY: Attribution.

- Sunil Kumar Singh, Work by Spring Force. April 14, 2013. Provided by: OpenStax CNX Located at: https://cnx.org/contents/adfec046-8a7c-462a-9f0a-e771ee654e5d@5. License: CC BY: Attribution.

- Pressure. Provided by: Wikipedia Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pressure. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike.

- cylinder. Provided by: Wiktionary License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike.

- integration. Provided by: Wiktionary License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike.

- revolution. Provided by: Wiktionary License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike.

- Area. Provided by: Wikipedia License: CC BY: Attribution.

- Area. Provided by: Wikipedia License: CC BY: Attribution.

- Integral calculus. Provided by: Wikipedia License: CC BY: Attribution.

- Area. Provided by: Wikipedia License: CC BY: Attribution.

- Shell method. Provided by: Wikipedia License: CC BY: Attribution.

- Sunil Kumar Singh, Work by Spring Force. April 14, 2013. Provided by: OpenStax CNX Located at: https://cnx.org/contents/adfec046-8a7c-462a-9f0a-e771ee654e5d@5. License: CC BY: Attribution.

- Solid of revolution. Provided by: Wikipedia License: CC BY: Attribution.

- Solid of revolution. Provided by: Wikipedia License: CC BY: Attribution.

- Solid of revolution. Provided by: Wikipedia License: CC BY: Attribution.